Urban Square: Cradle of Social Changes

Public space is the place for myriad of gatherings, political or otherwise. It is indispensable for democracy both as a symbolic gesture and as a viable arena for levée en masse.

Independence Square. Kiev, Ukraine. During a social movement called “Smile Ukraine! Smile overcomes a crisis!” Taken on April 22, 2009 Right: Three months after a political crisis erupted leaving dozens dead. Taken on February 20, 2014. Image source: Sergei Supinsky, Bulent Kilic/AFP/Getty Images via The Atlantic Monthly

Cities are living organisms each harbors unique, dynamic spaces and networks. The development of urban public space is informed by its’ geology, typography, resources, history, culture, and perhaps above all: governance. The physical manifestation of the city and its’ complex nature is ever-evolving, adaptive, and transformative. This adaptivity can prove to be especially potent, as it gives a city the capability to influence the distribution of political and socio-economical power. Public spaces have potential to further the prosperity of inhabitants or to maintain the status quo for those in power.

In the February issue of the Atlantic Monthly, Matt Ford examined the power of assembly in public space and reviewed a correlation between built form and political purposes in authoritarians states.

“Cairo’s layout also made Tahrir Square the perfect place to launch a revolution. Centrally located in Egypt’s largest city, Tahrir sits near the Egyptian parliament, Mubarak’s political party headquarters, the presidential palace, numerous foreign embassies, and hotels filled with international journalists to broadcast footage of the protests for audiences around the world. After Mubarak stepped down, large public squares in other Arab capitals became revolutionary battlegrounds as well.”

In another word, the perfect stage was set for the modern era.

Historically, public places have acted as epicenters of political moments. Aided by social media, the organization of public gatherings have taken on an entirely new dimension. These spaces no longer need to be centrally located; they are sometimes networked throughout a region with multiple nodes — they are interconnected neighborhoods with agent of change. However efficient or inefficient, the Occupy Wall Street movement was an ultimate expression of democracy. The organization of the movement occurred though conversations and consensus. Since the early days of the movement, the weekly public meetings were held at Tompkins Square Park. The movement was horizontal in hierarchy which required public space for assembly. New York City lacks the revolution launch pad that comparable to Tahrir Square in Cairo or Independence Square in Kiev. The search of a home played a pivotal role in defining the Occupy Wall Street movement.

In New York City, municipally owned parks close after dusk. During the summer of 2011, while the Occupy movement was without a home, general assembly was held in a handful of public parks. The movement’s Tactical Committee learned that privately owned public space (POPS) in New York City are not subject to public park curfew. City Planning Commission in 1961 devised a scheme to provide more public park by way of public / private partnership. This zoning laws incentivized developers to provide publicly accessible space by allowing more build-able space. These zoning laws required owner of Zuccotti Park to keep the park open for “passive recreation” twenty-four hours a day. This loophole provided OWS a home and the rest is history.

Public space is the place for myriad of gatherings, political or otherwise. It is indispensable for democracy both as a symbolic gesture and as a viable arena for levée en masse. People design spaces, and spaces facilitate activities of the people. Designers, in turn, are well positioned to be pivotal agents of social change — a role that must have been unimaginable for the designers of Zuccotti Park.

REFERENCES:

“Pre-occupied: The origins and future of Occupy Wall Street” – Mattathias Schwartz, The New Yorker.

“A Dictator’s Guide to Urban Design Ukraine’s Independence Square, and the revolutionary dimensions of public spaces.” Matt Ford, The Atlantic Monthly.

The People’s Library at Occupy Wall Street. Zuccotti Park, New York City. Taken on November 2, Day 47 of Occupy Wall Street. Image source: David Shankbone/Wikimedia Commons.

Via: Graphically In-between

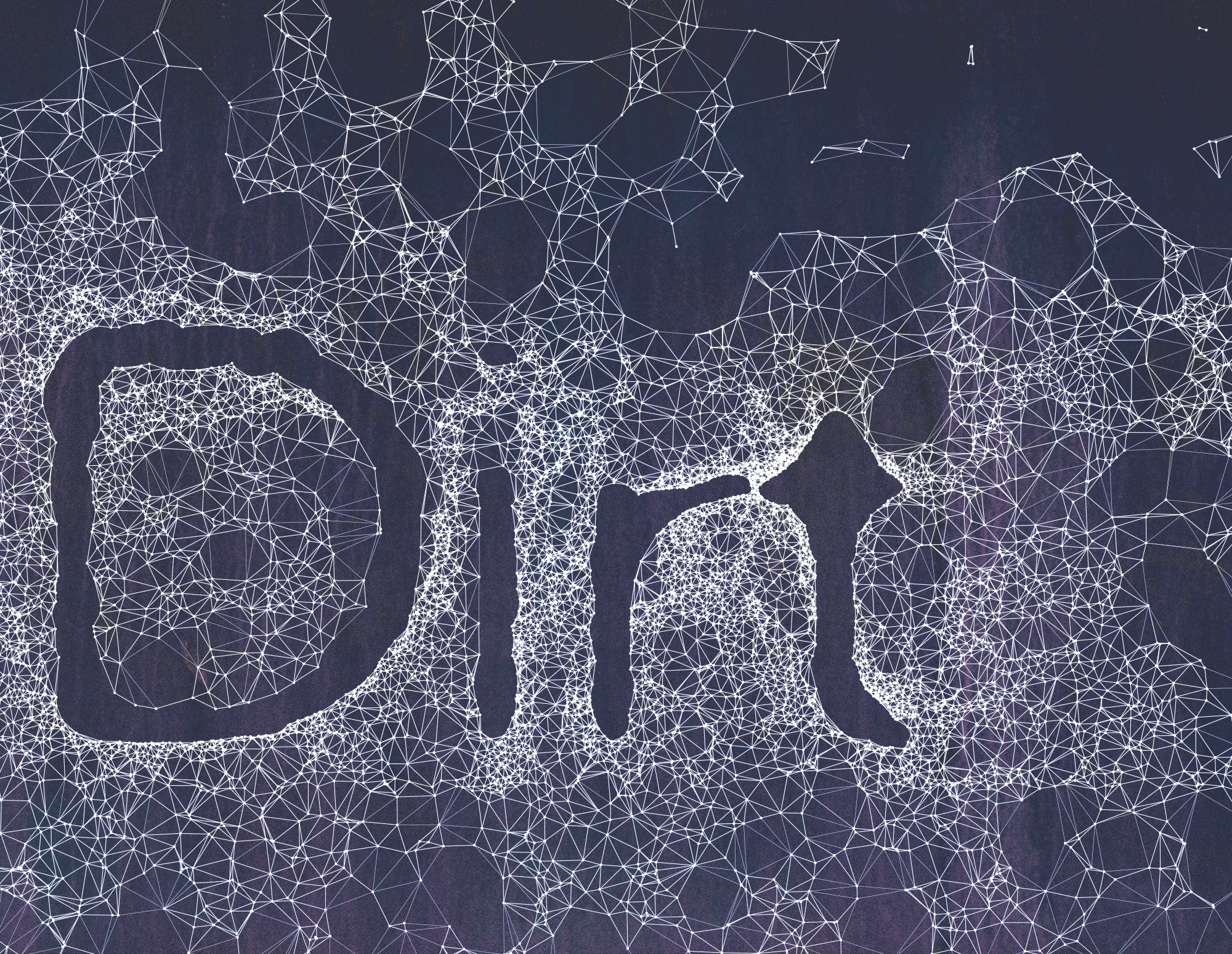

We think of dirt as a subversive form of communication, as a course in which cities are developed, as an iterative method of production, as elements or raw ideas, and finally, the most familiar interpretation of all: dirt as a fertile and tangible medium. The five distinct topics, each have their own set of visual and visceral associations. The challenge is to find a cohesive way to present these graphical affiliations for each chapter in a unifying fashion.

I have always thought of designing the look and feel of the book as a bit of a bipolar endeavor. Content wise, the book is very diverse. We think of dirt as a subversive form of communication, as a course in which cities are developed, as an iterative method of production, as elements or raw ideas, and finally, the most familiar interpretation of all: dirt as a fertile and tangible medium. The five distinct topics, each have their own set of visual and visceral associations. The challenge is to find a cohesive way to present these graphical affiliations for each chapter in a unifying fashion.

How does one tackle that? Finding a design language that can serve as a master framework for all 5 chapters? With a neutral, non-interpretive, clinical font like Helvetica? No. Instead, we celebrated the polarities. Essentially finding subtle ways to subvert traditional book designs. We first try to understand it, then dirty it up. We wanted it to look familiar but just doesn’t look quite right. So, we cultivate the jolie-laide {Jolly Led}, the ugly-beautiful lady, the point of tension, a balanced imbalance.

Susannah Brewster with Lisa Schwert, Book Cover of "Dirt" (2012).

Lily Jencks, An Ornament of Sustainability (2008).

You will notice that we used Garamond, an old French font from the 1500s, then juxtapose Garamond with a san-serif font—variation of Helvetica with rounded corners. The round corners are supposed to resemble a worn out metal type from yesteryear. You may notice that we have lots of hanging punctuations in paragraphs. Punctuations that are thrown out of the column grid is something you don’t often see in the age of inDesign and digital tablet publication. It’s very subtle, but the mechanical and intentional imperfection is enough to drive my fellow editor Phillip crazy. You will notice that our tessellated cover looks a bit like a sand formation that verging on complete entropy or you can think of it at it as snap shot of constellations in the evening sky. And lastly, you notice that our logo. You can think of our logo as emerging forms or a gummy bears melting away in a microwave.

So, graphically, we cultivated the in betweens. It is half full or is it half empty? It depends on the mode of narration of each chapter and each article. And at the end, It all depends on you the reader, it depends on your point of view.